Despite the fact that it happens to every single one of us and is as every bit as natural as birth, very few among us are properly prepared for death—whether our own death or the death of a loved one.

Yet the pandemic might be changing this.

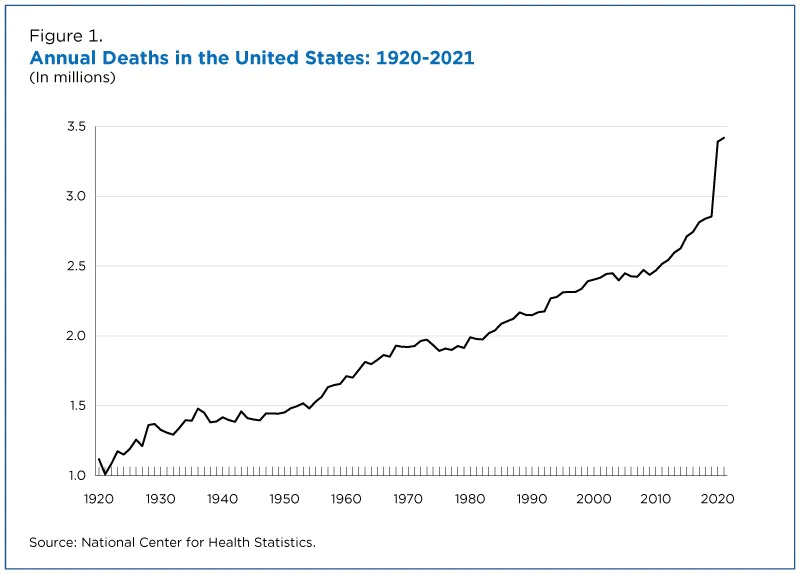

According to Census figures, the pandemic caused the U.S. death rate to spike by nearly 20% between 2019 and 2020, the largest increase in American mortality in 100 years. More than two years and 1 million deaths later, it’s more clear than ever that death is not only ever-present, but a central and inevitable part of all our lives.

Some in the end-of-life industry believe that the pandemic’s massive loss of life has created an opportunity to transform the way we interact with death, grief, and all of the other issues that arise with the loss of a loved one. Seizing the moment, one startup recently launched Empathy, an AI-based platform designed to help families navigate the death of a loved one. “We’re on a mission to change the way the world deals with loss,” reads Empathy’s ‘About Us’ page. The company’s CEA and Co-Founder, Ron Gura echoes this sentiment:

“For far too many, COVID-19 has been a terrible reminder that death and loss are all around us. But it also represents an opportunity to shift public perception, to bring a topic that has been for far too long shrouded in darkness into the light of day, where we can fully examine it and figure out how best to help those who have to shoulder its burdens.”

– Ron Gura, Co-Founder of Empathy

Determining Death’s True Cost

The death of a loved one generates a cascade of emotional, logistical, and financial challenges for those left behind. To further shed light on just how vastly unprepared most of us are when dealing with death, in March 2022 Empathy released its first-ever Cost of Dying Report. In partnership with Goldman Sachs, Empathy’s report surveyed more than 2,000 Americans—each of whom had lost a loved one in the last five years—to get a clearer picture of dying’s true cost to families.

The report looked not only at the financial burden dying brings, but also at the cost in time, stress, harmed productivity, and strained interpersonal bonds. Complete with insights from advisors, partners, and experts in bereavement, the Cost of Dying Report “bust open the taboo that has for too long kept it out of the public consciousness,” said Gula.

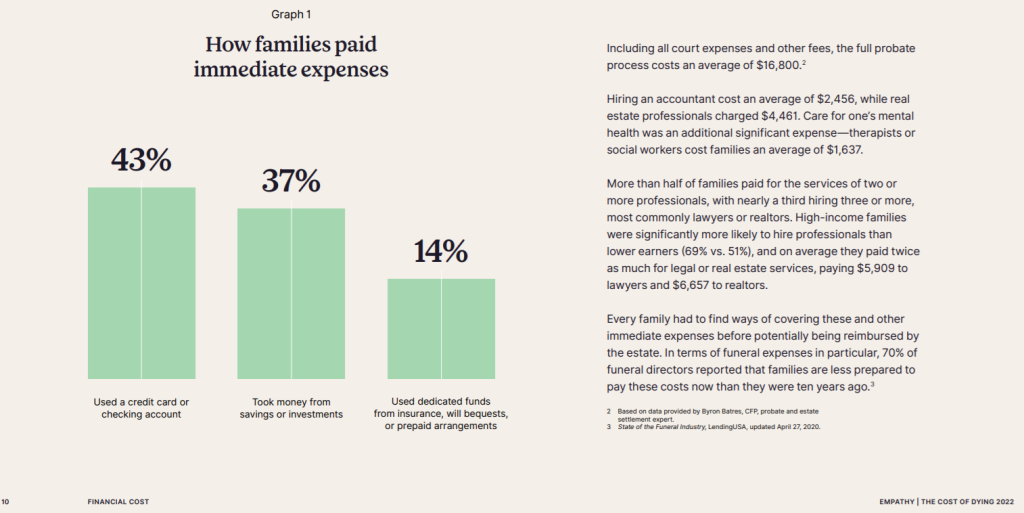

Empathy found that the average total bill of death is $12,702. The average cost of a funeral was $7,267—according to the National Funeral Directors Association, that cost has risen 7.6% in the last 5 years. On top of the funeral, families paid an average of $5,846 to hire additional professionals such as lawyers, financial advisors, therapists, and realtors.

The average cost of lawyers fee’s following the death of a loved one was $3,910. This amount, however, is nearly doubled for estates that required the court process of probate, as was the case for one-third of families surveyed; the average total cost to complete probate for the families surveyed was $16,800.

Beyond the purely financial, The Cost of Dying Report found that families spent 13-20 months completing end-of-life tasks for their deceased loved ones. Study participants clocked an average of 420 hours of work to handle an estate with around five phone calls a week (26 hours per month on the phone!) The majority of families also said it took longer to much longer than expected to wrap up all of the necessary tasks.

In the words of contributing attorney Avi Z. Kestenbaum, “every estate is settled eventually. Even the most complex one. But it is very often a long road to get there—and if you think you know how long, you probably don’t.”

Paying The Final Bill

So how do families cover all of these expenses? Unfortunately, the report found that only one in seven families had the costs associated with their loved ones’ death prepaid, or were able to use inherited funds. Additionally, more than 50% of families had to deal with estates that included debt. To foot the bill for these expenses, 36.1% of respondents used their own savings or investments, while 42.4% used their checking accounts or credit cards.

For most families, the financial costs associated with loss were exacerbated by a lack of information about exactly how much money they should expect to spend, according to physician Shoshana Ungerleider, MD, in the report’s section on death’s financial cost. Compounding that stress, Ungerleider says, was the families’ fear of making a mistake that will make their financial burden even worse.

“A majority of families find themselves unprepared for and under-informed about the real financial costs of death, with few available resources for finding out,” writes Ungerleider. “They can spend months or years terrified that a wrong move will wipe out their inheritance or even their own savings.”

As an example of what such a mistake might look like, Ungerleider notes that a lack of proper estate planning can lead to the deceased’s home being seized after death for Medicaid Recovery, even if the family member who was their primary caregiver is still living in the home.

Preparing For The Inevitable

Fortunately, there are ways you can dramatically reduce the financial, logistical, and emotional burden for your loved ones upon your death. There are strategies to help your family to avoid the time, expense, and emotional burden associated with probate, such as by placing assets in a properly created and maintained revocable living trust. We also offer planning strategies that can help you and/or your senior parents qualify for Medicaid and other benefits, without putting the family home or other assets at risk.

Our end-of-life planning also includes asset protection, avoiding family conflict, funding long-term care, and estate tax mitigation, just to name a few. Sit down with us for a Family Wealth Planning Session to find the most effective and affordable planning solutions for you and your family.

The more you prepare for your own eventual death and learn about the process, the more support you can offer friends and family members who have recently lost a loved one. As Kestenbaum notes, “as a society, then, we can be much more aware not only of the stress that our bereaved friends, neighbors, coworkers, or employees are under, but also understand that the pressure will persist for a very long time. So even one year later, try to ask: How are you? Is there anything I can do to help? That will be very meaningful.”