Part One

In the past several decades, technological advancements have radically changed our world. Developers have continuously pushed the horizons of possibility, leaving consumers scrambling to keep up with the latest gadgets and developments. In this whirlwind of perpetual motion, we have taken the intangible – that which exists only in code, witnessed only on our screens – and given it real value. It is an exiting time to be alive. It is a critical time to incorporate this new, digital world into your estate plan.

Without properly addressing your digital assets in your estate plan, you risk losing all or some of those assets after you pass. Just locating and accessing your digital assets can be a major headache – or even impossible – for your loved ones following your incapacity or death. If your heirs do manage to access your accounts, they may discover they’re violating privacy laws or the terms of service governing those accounts. You may also have certain digital assets that you don’t want your loved ones to inherit, so you’ll need to take steps to restrict or limit access to those assets.

In this technological arena of digital assets, there are several special considerations to be aware of.

Types of Digital Assets

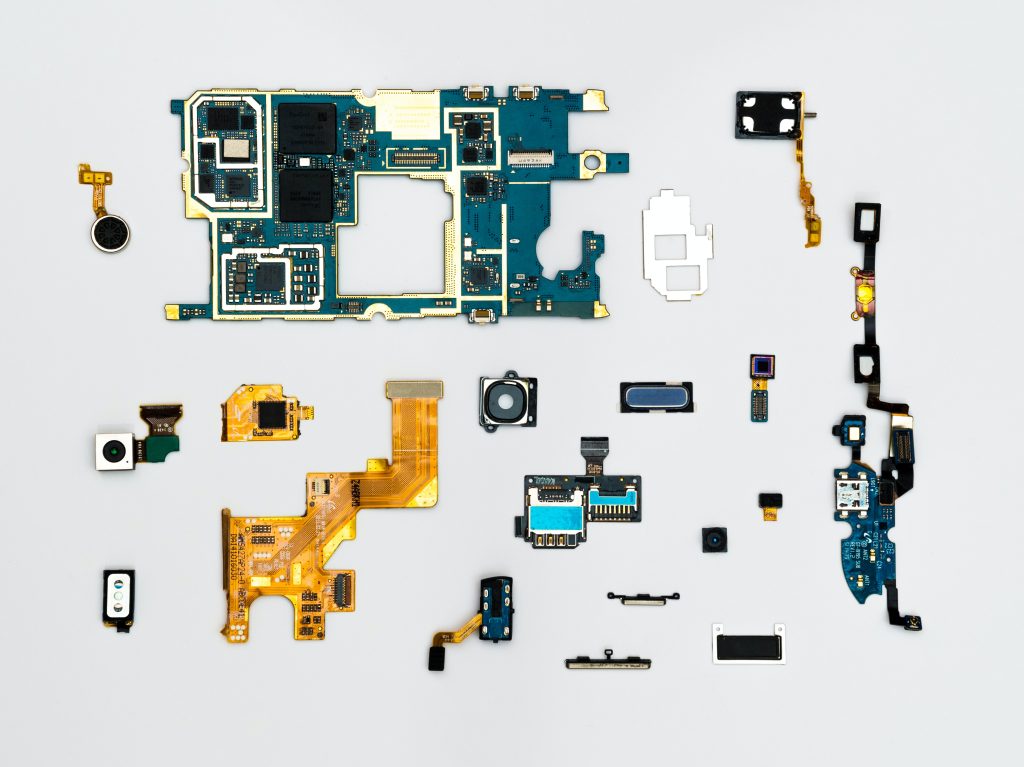

Digital assets include a wide array of digital files and records that you have stored in the cloud, on smartphones and mobile devices, or on your computer. When it comes to estate planning, your digital assets will generally fall into two categories: those with financial value and those with sentimental value, which could mean far more to the people you love (and your future generations) than the assets with financial value.

Financial Vs. Sentimental

Digital assets with financial value include cryptocurrency like Bitcoin or Ethereum, online payment accounts like PayPal or Venmo, loyalty program benefits like frequent flyer miles or credit card reward points, domain names, websites and blogs generating revenue, as well as other intellectual property like photos, videos, music, and writing that generate royalties. Such assets have real financial worth for your loved ones, not only in the immediate aftermath of your death or incapacity, but potentially for years to come.

Digital assets with sentimental value include email accounts, photos, video, music, publications, social media accounts, apps, and websites or blogs with no revenue potential. This type of property typically won’t be of any monetary value, but it can offer real sentimental value and comfort for your family following your death and inform future generations in ways you may not have considered.

My parents exclusively used film cameras – most of my childhood memories are stored in disorganized boxes in my mother’s closet. Then there’s the rare, tattered envelope with photos of my parents when they were my age, just a couple pictures here and there. Those are the photos I cherish most. My generation, however, document the majority of their experiences with their cellphones. The photos our children will cherish are on our personal devices, Google Drive, Cloud, or that password protected hard drive. Imagine if you could scroll through your mother or grandmother’s Cloud, looking at all the moments, silly and serious, she captured throughout her life. Imagine if you could see the world through your great-grandfather’s eyes. Those are the sentimental digital assets.

Do You Own Or License The Asset?

The financial digital assets can be a bit more tricky; you don’t actually own many of your digital assets at all. For example, you do own assets like cryptocurrency and PayPal accounts, so you can transfer ownership of these items in a will or trust. But when you purchase some digital property, such as Kindle e-books and iTunes music files, you only actually own a license to use it. In many cases, that license is for your personal use and is non-transferable.

Terms of Service Agreements

Whether or not you can transfer this licensed property depends almost entirely on the account’s Terms of Service Agreement (TOSA) to which you agreed (or more likely, simply clicked a box without reading) upon opening the account. Many TOSAs restrict access to accounts only to the original user, some allow access by heirs or executors in certain situations, and others say nothing at all about transferability.

Review the TOSA of your online accounts to see whether you own the asset itself or just a license to use it. If the TOSA states the asset is licensed, not owned, and offers no method for transferring your license, you’ll likely have no way to pass the asset to anyone else, even if it’s included in your estate plan.

To make matters even more complicated, though your loved ones may be able to access your digital assets if you’ve provided them with your account login and passwords, doing so may violate the TOSA and/or privacy laws. To legally access such accounts, your heirs will have to prove they have legal authority. Until recently, this process was a huge legal grey area—lawmakers have also been scrambling to keep up with technology.

Thankfully, most states have adopted laws that help clarify how your digital assets can be accessed and disposed of in the event of your death or incapacity.

The Law of the Digital Land

Until very recently, there were no laws governing who could access your digital assets in the event of your incapacity or death. As a result, if you died without leaving your loved ones your usernames or passwords, the tech companies who controlled the platforms housing the assets would often delete the accounts or leave them sitting in a state of online limbo, inaccessible to your family and friends.

This gaping hole in the legal landscape caused considerable heartbreak for families looking to collect their loved one’s digital history. It also created major frustration for the executors and trustees charged with cleaning up the estate and led to the loss of an untold amount of tangible and intangible wealth. The federal government finally stepped in to find a solution for this problem starting in 2012, and by 2014, the Uniform Law Commission passed the Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Access Act (UFADAA).

A revised version of this law, the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA) was passed in 2015, and as of March 2021, it has been adopted in all but four states. The law lays out specific guidelines under which fiduciaries, such as executors and trustees, can access your digital assets. The Act allows you to grant a fiduciary access to your digital accounts upon your death or incapacity, either by opting them in with an online tool furnished by the service provider or through your estate plan.

Three Tiers of Access

The Act offers three-tiers for prioritizing access. The first tier gives priority to the online provider’s access-authorization tool for handling accounts of a decedent. For example, Google’s “inactive account manager” tool lets you choose who can access and manage your account after you pass away. Facebook has a similar tool that allows you to designate someone as a “Legacy Contact” to manage your personal profile.

If an online tool is not available or if the decedent did not use it, the law’s second tier gives priority to directions given by the decedent in a will, trust, power of attorney, or other means. If no such instructions are provided, then the third tier stipulates the provider’s TOSA will govern access.

The bottom line: If you use the provider’s online tool—if one is available—and/or include instructions in your estate plan, your digital assets should be accessible per your wishes in most every state under this law. However, it’s important that you leave your fiduciary detailed instructions about how to access your accounts, such as usernames and passwords.

Make a Plan for Your Digital Assets

Leaving detailed instructions is the best way to ensure your digital assets are managed in exactly the way you want when you die or if you become incapacitated. In the second part of this series we’ll offer practical steps for properly including your digital assets in your estate plan. Meanwhile, feel free to call or email us with any questions you may have.